Mirrorless hasn’t only won the battle, it’s won the war. Last year — 2020 — was a landmark as more mirrorless cameras were shipped than DSLRs. It is the primary design choice for manufacturers and is therefore the future of the camera. However, the future of photography undoubtedly lies with the smartphone.

It appears so obvious looking back over the last ten years, that it seems inconceivable that mirrorless wasn’t considered the future of camera design when it first appeared. However, the vested interests of CaNikon kept the DSLR dream alive — along with their income streams — which let other manufacturers dabble to see what the market was interested in. And dabble they did after Olympus and Panasonic debuted Micro Four Thirds, with Sony, Nikon, Pentax, Canon, Fuji, and Leica all introducing new systems. This has to be viewed within the context of global camera shipments which peaked at 121 million units (¥1643 million) in 2010. OK, of these some 109 million were integrated cameras — high quantity, low value — but it did generate significant income and profit for manufacturers which in part funded the system development. But as soon as that spike in income had arrived, it rapidly began to disappear with 2020 marking a new low point of 9 million units shipped (¥420 million).

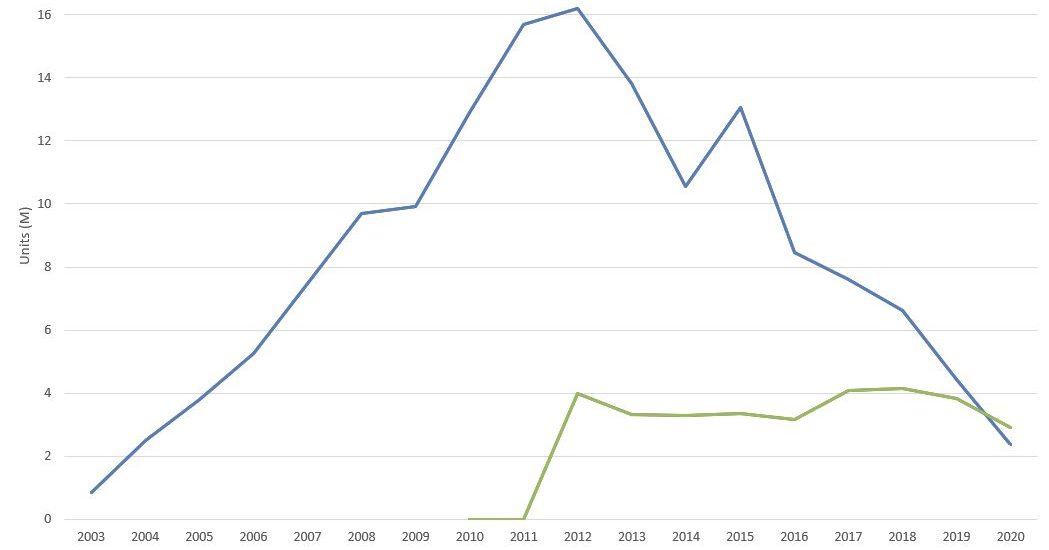

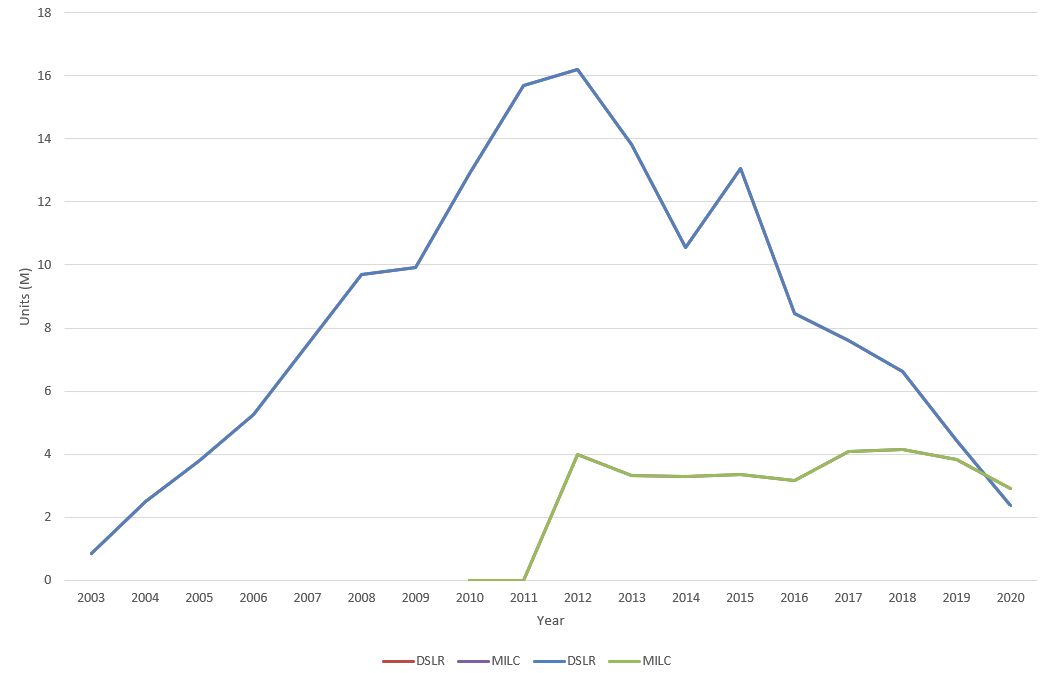

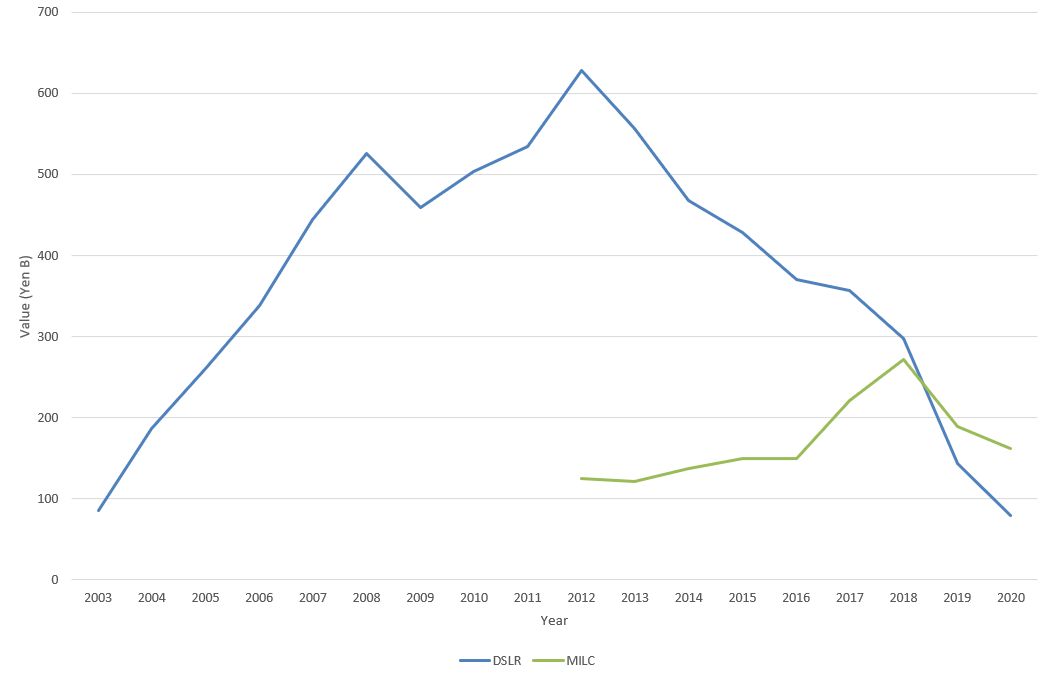

The following year, 2011, also saw mirrorless make their first appearance in CIPA data (below) which showed 4 million units shipping, meaning that uptake was rapid by consumers and principally focused around Panasonic, Olympus, and Sony. While DSLR shipments imploded, mirrorless has remained flat in a falling market meaning that they made up an increasingly larger share. 2020 was a landmark year in that more mirrorless cameras were shipped than DSLR; 33%, as opposed to 27%, of total shipments.

This is important enough in itself, however, it is the financials that are more impressive. Mirrorless was close to DSLR shipment values by 2018 and exceeded them in 2019. By 2020 they made up 54% of all camera shipments, compared to DSLR’s 25%. Of course, by this point, both Canon and Nikon had released their own mirrorless systems and essentially stopped further DSLR development while reducing production. While it’s true that consumers wanted to buy mirrorless systems, manufacturers also stopped making them in volume.

Will manufacturers stop making DSLRs? Of course not. As long as there are a minimum viable number of customers, then someone will plug that gap. Apparently, that’s Pentax at the moment. Not only that, but there will continue to be a large number of active DSLR shooters who will want to buy lenses and accessories. You wouldn’t necessarily say that mirrorless won a decisive battle in one-up-manship, but rather slowly chipped away at that seemingly impenetrable DSLR exterior. The biggest slug came with Sony’s a7 in 2013 showing that a mirrorless full frame model was viable; in fact not one model, but three. The battle was won by 2016 at the latest as Canon and Nikon pivoted into developing their own systems. Was it that cameras were smaller and lighter? Or those significant improvements in on-chip focusing brought significant advantages? Or that shorter flange distances allowed a range of interesting lens designs and the adaptation of existing lenses? Or maybe high burst rates? Or perhaps it was just because it was a new system. Either way, the traction is now there and DSLRs have become niche.

Mirrorless is the future of camera design.

Long Live the Smartphone

Mirrorless cameras are only half of the photography equation. That dramatic drop in CIPA camera shipments from 121 million in 2010 doesn’t mean there are fewer cameras shipping. Far from it, as in 2019 some 1,500 million smartphones shipped, depending upon whose figures you believe. Every single one of those had a camera in it. It’s perhaps self-evident that the smartphone has all but killed the camera industry, but the scale and enormity of putting a camera in the hands of 7.5 billion people or about 96% of the global population is truly astonishing. We are genuinely at a point where virtually everybody takes a photo; no wonder Google stopped unlimited free photo storage!

Now obviously smartphones do far more than take photos, but this remains an important component of any phone design to the point that there has been a continual arms race since the original iPhone which shows no sign of abating. Talking of Apple, they held a 14.5% market share in 2019, lagging behind Huawei (17.6%), and Samsung (21.8%). Does that sound familiar? Yes, three companies control some 54% of the smartphone market so what they do with their cameras is critical not just to other smartphone manufacturers but also to camera manufacturers. In fact, while we see some inroads in partnerships between smartphone and camera manufacturers, it’s surprising this isn’t more widespread and, indeed, that the partnerships don’t work in both directions. Hasselblad recently partnered with OnePlus, but we have seen Leica and Huawei, Zeiss with Sony (and a number of others), and possibly Samsung with Olympus.

What’s interesting is that the developments we are seeing at the moment in some ways mirror the introduction of the Kodak Brownie in 1900. Up to this point, technological development had been rapid but largely focused on gradual improvements to the large format camera. Photography was an expensive undertaking and the Brownie democratized it to the extent that, while not trivial in cost, anyone could afford it (it was $1 at release, equivalent to $31 today). For example, it was targeted at soldiers and even children. The Brownie grew out of the development of roll film and the realization that everything for photo taking could be included in the (cardboard) box and then sent back to the manufacturer for processing. This then led to making a loss on the sale of the camera but a profit on the film and processing. Two strands of photography were subsequently developed based around large format cameras and low-cost roll film cameras. In some ways, those strands were at least partly re-unified with the release of the Leica 1 in 1924 when 35mm roll film was partnered with technologically innovative development.

Are we seeing the same with the smartphone? Two drivers are at play here: firstly the need for eye-popping images that look great on social media and secondly tight design requirements. The latter involves low-cost, small, devices that have fixed lenses. Smartphone manufacturers are aware that to get better images they can — to a certain extent — compute their way out of the problem, a charge that has been led by Google. However, they are inevitably restricted by the hardware they have at their disposal. Involving camera manufacturers is, therefore, a sensible decision.

The different design criteria have led to a divergent focus for camera development, one that is arguably now the direction that photography is taking. Smartphone manufacturers are incorporating new and creative hardware designs to work alongside their software implementations. What we are not seeing is camera manufacturers developing innovative standalone cameras. Computational photography has been a core aspect of photography in smartphones for a decade, yet we have seen limited implementations by camera manufacturers and certainly nothing that rivals the likes of Apple or Google. This is now becoming a yawning gap that has the potential to make camera manufacturers irrelevant or even allow a new manufacturer to enter the marketplace.

We will always need high-end cameras for high-end photography commissions, but the gap between the smartphone and camera has shrunk considerably to the point where it is indistinguishable for many applications, something that Ben Von Wong pushed with his commission for the Huawei P8.

Lead image courtesy Pexels via Pixabay, used under Creative Commons.