The once-stodgy enterprise server platform used to have to stretch to do everything, but is now a high-performance system building on the best of Azure for an ‘insanely ambitious’ future of collaboration and content management.

” data-credit=”Image: Microsoft”>

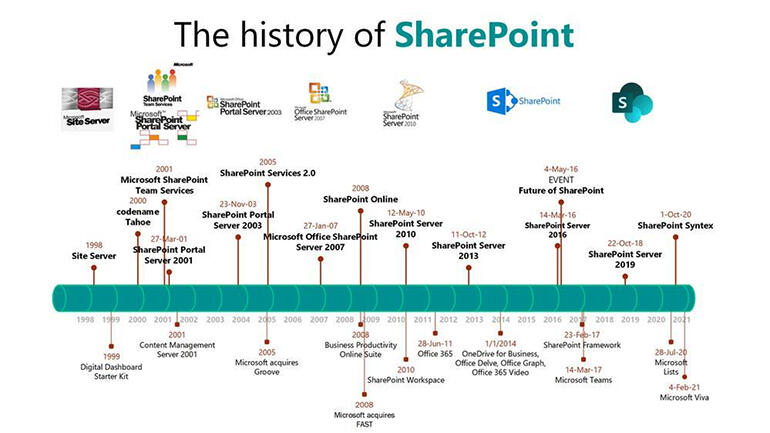

20 years on from SharePoint Team Services and SharePoint Portal Server: a birthday party.

Image: Microsoft

As the back end for Teams, Microsoft’s SharePoint has been in some ways the sleeper hit of the pandemic. While the technology powering it has changed beyond recognition from the 2001 SharePoint Portal Server release, the original ideas of content collaboration, enterprise search and information organisation that made it the fastest Microsoft product to generate a billion dollars have remained intact.

The way the underlying SharePoint architecture has changed reflects both technology and culture changes within Microsoft over the years. Talking to TechRepublic just after the 20th anniversary celebrations for SharePoint, Jeff Teper — now corporate vice-president for Microsoft 365 collaboration and responsible for Teams, SharePoint and OneDrive — suggested that it summed up “my twenty-year journey from top-down waterfall and chaotic agile, to a middle way, which is intentional planned but loosely coupled execution.”

From the web to the cloud

” data-credit=”Image: Microsoft”>

Jeff Teper, corporate VP at Microsoft: “You can be visionary, you can stake out a vision for the future, but you can be empathetic and humble.”

Image: Microsoft

SharePoint’s roots go back to Microsoft’s 1997 Site Server for content management and websites, and the Office XP development cycle. Pitched to Bill Gates in 1997 or 1998, Tahoe was about taking collaboration in Office beyond the email, calendar and task lists that Exchange already offered, to deliver content collaboration, document management, indexing and search alongside portals. The slide Teper showed Gates had three overlapping circles labelled Document Management, Portal and Collaborative, and a lot of references to Office and Exchange (the three circles in the new Fluent design SharePoint logo might be a subtle reference to that).

“One of the names we toyed with at the beginning was Office Server: that Office needed a server for people to publish documents to and create team spaces around,” Teper told us. “It became successful because we had this magical combination of a bottom-up experience that was free and viral — anybody can make a SharePoint site — and then SharePoint Portal for top-down knowledge management, aggregation, more high-value document workflows and so forth.”

The combination of organic adoption, management tools and opportunities for the ecosystem created a virtuous cycle of growth, but it also required SharePoint to act as an entire platform.

In 2018, Teper described SharePoint to us as “the universal content collaboration solution: all kinds of content in all types of context”. That might sound ambitious, but the arrival of the cloud, and a new culture of collaboration between different teams within Microsoft, had allowed the SharePoint team to actually narrow their focus.

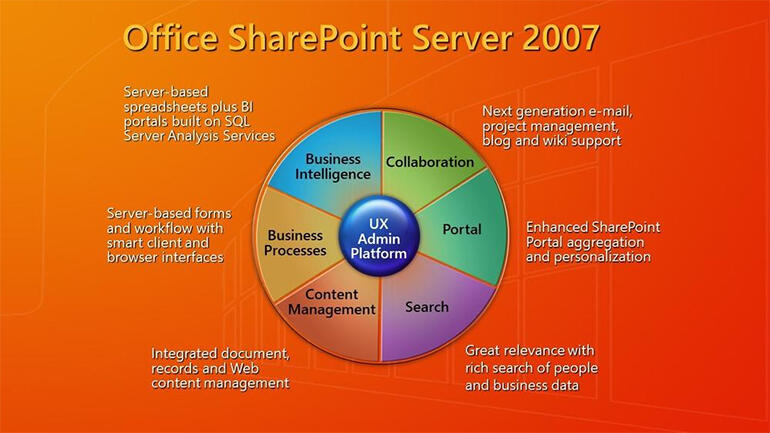

“In a pre-cloud world, SharePoint had to stretch and be everything: it had to be all things to all people, app and platform,” Teper explained. Enterprise IT teams would frequently skip product releases, alternating between an Exchange deployment in one release and a SharePoint deployment in the next; customers made it clear to Microsoft that they didn’t have the resources to add another server. “So we put a lot of stuff in SharePoint: in the 2007-2010 timeframe that was InfoPath and BI, and it also had to be almost the IaaS and PaaS for the on-prem world because ASP.NET was too low-level — it was a developer thing. Both Microsoft and other companies just threw everything into SharePoint, because it was already this fabric that was deployed in the company.”

Moving to cloud had two benefits, Teper said. “One, customers didn’t have to deploy the services, so we could be more loosely coupled in Microsoft. And the second is that Azure filled the need for a horizontal platform for first- and third-party apps better than SharePoint.”

The idea of Office 365 was controversial, with customers and with partners who were afraid that the move to cloud would take away their business. Teper had to point out to them that deploying commodity services on Exchange and SharePoint was not the way to differentiate. “It was crazy; the top thousand companies in the world were duplicating each other’s work to deploy SharePoint and Exchange and chewing up a big portion of their budget. I said it was incredibly insane to have all these data centres around the world running at 5% utilisation, that are not well run, on older hardware. If we and our peers can run data centres at higher utilisation rates at higher scale, and we can do the deployment work once as opposed to every IT organisation, we’ll get data content out to people faster and a much higher portion of the IT budget, can go to company-unique work.”

Teper famously came out of a customer meeting at Redmond to tell then-CEO Steve Ballmer that Microsoft needed to move ahead on SaaS even though those customers weren’t planning to adopt cloud. “It was a classic Innovators Dilemma where customers won’t always articulate their unmet need — which was they were not getting the ROI — out of their IT spend. You, as a technology company need to lead your customers, even if they fight you a little bit.”

Leading the customers didn’t mean getting rid of server products in 2012 — and it still doesn’t: developments in technology need to be accompanied by an understanding of the people and organisations that will use them, Teper insists. “In tech, we need to not be so arrogant; we’re all attracted to this industry because we want to embrace change and we love the pace of change, but change management needs to be more grounded in how long it will take people to get through it.”

“You can be visionary, you can stake out a vision for the future, but you can be empathetic and humble. It’s not this trade-off that you have to be completely wishy washy and say ‘yes, you’re the customer, you’ll tell us the future’, but you also don’t need to be a jerk and say ‘this is the future, get with it now’.”

” data-credit=”Image: Microsoft”>

Jeff Teper on pre-cloud SharePoint: “It had to be all things to all people, app and platform.”

Image: Microsoft

Slimming down SharePoint

The shift to cloud proved extremely profitable for the partners who had complained about the idea, and also allowed companies to change the way they did outsourcing. “Companies that had outsourced to an IBM or EDS and sadly outsourced their technical expertise, realised that was a mistake; they needed very sophisticated technical people in their team, who could create employee-engaging experiences, customer transformation, business transformations on technology. And so we found our way through this mistaken period of outsourcing your entire IT department to a better model, which is to let people run the infrastructure in the cloud, and have technical people on your team that are able to absorb all this technical change and use it to improve your employee and customer engagement.”

It also freed SharePoint to focus on its roots in portals, content collaboration, document management and search, which meant that new features could focus on those areas.

“New innovations like Stream — it’s content! Videos are content, and you want to secure and manage them in a consistent way; they’re just files. So we’re building that on SharePoint. Things that are not content like Dynamics; that’s built on its own data model.”

SharePoint used to have its own workflow model and its own design tool, which also didn’t make sense in a cloud world. “In 2015 I had a conversation with James Phillips, who runs the business application group, and I said it’s crazy that we’re doing this one-off workflow and forms and app designer for SharePoint; I want to I leverage something that addresses multiple scenarios.”

SEE: Office 365: A guide for tech and business leaders (free PDF) (TechRepublic)

Instead of SharePoint and Dynamics both having their own separate design and workflow environments, they use what became Power Apps and Power Automate.

Many Power Apps create document workflows, so SharePoint is the most popular data source. “But there are complex customer tracking applications that are built on CDS, where SharePoint isn’t the right data store for that. We can go into our ecosystem with one tool strategy that spans line-of-business and content management, because you want a ubiquitous development tool and workflow engine that works with any data source.”

“Yes, I want SharePoint to be always neck-and-neck as the number-one data source, but it’s never going to be the only database in the world. Even I don’t have that ambition!”

Similarly, Teams, Power BI and Power Apps are all integrated. “It’s loosely coupled; Power BI can look at lots of different data sources and Power BI can embed in lots of different apps. But we did the last-mile work in both SharePoint and Teams that deeply integrate the Power platform.”

The architecture of SharePoint itself changed significantly because of the move to the cloud. At one point, SharePoint was running 15 different databases. “In SharePoint on-premises, each feature team could build their own SQL database, but when you build a large-scale cloud service where you want to do sharding and partitioning and so forth, and you care a lot about COGS and performance, you don’t want all these open connections to all these different databases.”

To deal with that, dozens of engineers spent several years on a project called MinDB, re-architecting the SharePoint content database for high performance and scale using Azure SQL Database — which now involves helping to build the underlying cloud services. “I have over fifty engineers who work in the SharePoint team who are working in the SQL Azure codebase, to make SQL Azure even more scalable, performant and cost-effective to run, because SharePoint is one of the biggest customers and a 1% difference for SharePoint, given the hundreds of millions of Microsoft 365 users, adds up to a ton of benefit. Similarly, in the file I/O layer, we’ve worked with Azure networking and Azure CDN. The HTTP stack that we get in the browser with Chromium Edge…we are making changes in pull requests to the Chromium code base so that we can upload files to SharePoint faster than things like Dropbox and Box and so forth.”

One of the authors of the operational transform algorithms that co-authoring in Office is based on now works in SharePoint, Teper noted. “We came up with this Fluid technology that leads to a new set of distributed data structures that will give us even faster co-authoring than what we’ve done and Google’s done. And what we did is map those structures onto the lowest level storage that we do on Azure Blob, so we can get speed-of-light performance.”

“We’ve got trillions of objects in Azure Blob [storage] in SharePoint out on disk in these data structures, so we can get them through the kernel onto the wire in an efficient format so these Fluid-based applications can use [the content].” Work on Fluid is continuing, and Teper promised some new Fluid-powered experiences coming to Office and SharePoint “in the next few months that will make this more tangible for people”.

Those architectural improvements meant SharePoint could go from 100 million users to 200 million users in a year without struggling, but they’re also a sign of big cultural changes inside Microsoft that enable this kind of collaboration between different products and services.

Connecting the graph

Two acquisitions that have been important to SharePoint encapsulate that culture change — and what it took to deliver the long-term vision of SharePoint.

The leaders of Yammer, David Sacks and Adam Pisoni, pushed the Office division to double down on both cloud and culture change. “They came in at a time where we needed to be challenged on how extreme we could be in our transition to the cloud. We were on a moderate-paced journey with Exchange and SharePoint in the cloud and they were telling us ‘you’ve got to go even faster; don’t wait for your customers, lead your customers.”

The Yammer technology itself also needed work. “That took longer than anybody expected,” Teper noted. “It’s not good or bad: this is exactly what you should do as a start-up. You should think about architecture a little bit but not over-optimise on it. You should optimise on product market fit and velocity, and maybe accrue some technical debt, and that’s brilliant. But when you’re trying to go from your 10 million users to 200 million users, you need the architecture and you need to retire technical debt. That took a while.”

Now Teper describes Yammer as “the social fabric that powers experiences across Microsoft 365”.

Standalone usage of Yammer is still growing and it’s integrated with Outlook, SharePoint and Teams. “Yammer is now growing like gangbusters,” Teper said, and the popularity of Teams helps rather than competes. “People get the idea that there’s the immediate circle of people I work with, it’s a team, and then there’s this broad open social conversation that’s more of a community.”

Sacks and Pisoni have moved on, but the CTO of FAST Bjørn Olstad is still leading that team — who created what’s now the Microsoft Graph. “They came in with the vision that experiences would be algorithmic, not just explicit search, but all experiences would be algorithmic.” That’s routine today, but it was a very new idea in 2008 that was hard to deliver without cloud.

“The problem was that companies couldn’t afford enough computing power on-prem to have enough data and for the algorithms to get better fast enough on the couple-of-years ship cycles,” Teper explained.

“Lo and behold, we make our way to the cloud, we try some things like Delve, machine-learning algorithms get better, computing power gets better and some things we wanted to make successful now are possible. So Viva Connections is a feed, based on the Microsoft Graph, which was the concept we launched with Delve, and SharePoint news and streaming videos and Yammer conversations are in that feed that’s tailored and targeted for you, leveraging that FAST technology.”

“Teams is the shell, the SharePoint team built the Viva Connections app, FAST gave us the feed and Yammer gave us the social conversations; it all layered up. If you ask, did I have this master plan ten, fifteen years ago? Not exactly at that detail, but it was the vision that if we could get social technology and search technology and content management to come together, we could do these kinds of things.”

SEE: 69 Excel tips every user should master (TechRepublic)

Going modular needed both the technology development and the culture change in the company.

“We needed to break down the technical and organisational silos in Microsoft to have these Lego blocks be very flexible and assemble them in a way that makes sense to users. We get some engineering efficiency out of this: we don’t want each team building its own social fabric or its own content management system or its own workflow engine. We have focused teams at Microsoft and then we can stitch them together. If you want a standalone Lists experience, we’ve got that. If you want a hub that brings it all together in Teams, we’ve got that. This modularity and flexibility is part technology and part culture and part user experience.”

Teper started his career at Microsoft in Office, where software was a monolith built using waterfall — a methodology leaders like Steven Sinofsky excelled at. “You come up with a great plan and everything shows up on one day.” That means thousands of people whose work is interdependent and very tightly coupled.

Working with the Yammer team on cloud services gave him experience of the other extreme. “Completely loose coupling, two to ten engineers, two to ten weeks, let the chips fall where they may.”

Now, he advocates for something between the two extremes. “You do need a plan. What are your business priorities, what are your user needs, what’s your information architecture and user experience, what’s your physical architecture? There are some things, like the work with Azure in the storage layer, that take years. So you need a business plan, a UX plan, a technical plan. It’s evolved by data and market conditions, but you do need a plan. But then wherever you can, make things loosely coupled and independent. Try to design for that, so you don’t need to have everything go right for anything to make forward progress, and you don’t need to have it all show up on one day for anything to make progress.”

The broader story of Viva is an example of that modular, loosely coupled approach. “We told a holistic, planned story but the pieces are shipping at different times. Some pieces are a little faster than others to market: it’s okay. We have a vision for Viva.”

” data-credit=”Image: Microsoft”>

20 years on from SharePoint Team Services and SharePoint Portal Server: a birthday party.

Image: Microsoft

Still growing

The SharePoint birthday party — appropriately organised by the community rather than Microsoft, for a product whose success has been strongly linked to the ecosystem of partners and consultants who build on and support it — was a chance to reminisce, but Teper pointed out that SharePoint is pretty sprightly for such a veteran product.

Depending on which metric you look at, SharePoint and Teams usage is up five, 10 or 50 times as the pandemic accelerated the journey to the cloud and modern mobile productivity, Teper said. “We’re doing millions of requests per second. SharePoint, in the twelfth month of its twentieth year, added more content each week than we had in the entire service five or six or seven years ago. We’re seeing petabytes of new content each day coming into the service.”

Treating Teams as a platform creates what he calls “the democratisation of collaborative applications, whether it’s Power Apps for line of business or SharePoint Framework for more content management. If you look at the success of Teams relative to other things in the marketplace, I think it validated that our approach of having an integrated set of collaboration tools with chat and meetings and files and more was the right approach.”

“We don’t have a SharePoint Designer any more: we gave that to the Power Apps team. We don’t have a low-level storage deployment fabric that was one-off to us. We bet on the Azure teams, but that let us do what you’re seeing now in Viva and Streams and Lists and Fluid. If you look at Lists, OneDrive and files and Viva, we’re creating more new experiences in SharePoint than ever before.”

“The inflection point was for us in 2015, 2016 when we said we’re going to be the world’s best and most flexible content management system, and we’re going to power these content-centric experiences, wherever the users are — OneDrive, websites, or in Teams. I think we re-found our soul, after a period where, because we were so successful, we were trying to be too many things to too many people. We’re back to something insanely ambitious, but we’re not trying to be everything.”